Art's Cruel Practice

Art's Cruel Practice

Art's Cruel Practice

by George Bataille

Unit 1: The Beautiful Corpse

How to Die in the Cannon Without Really Trying

Fall, 2025

Every semester, I ask my 101 students what they think art is. And every semester, I get the same answers:

"It's how you express yourself."

"It's how you engage with your community."

These are fine....human, earnest, I've nodded along, out of laziness, out of respect for the effort. I don't want to discourage, because I don't even know how to answer that question myself.

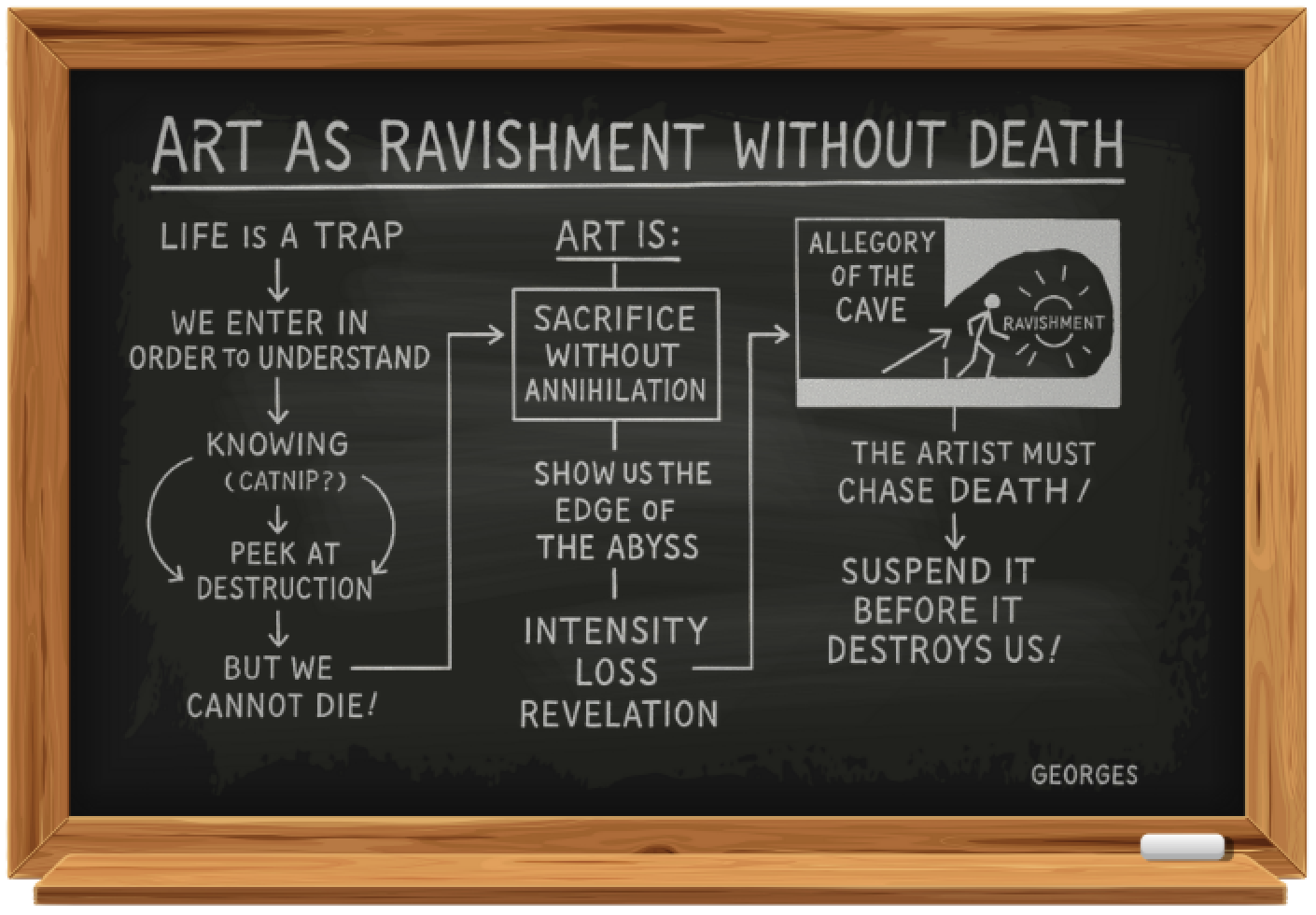

But in Art's Cruel Practice, Bataille comes not with expression or community, but with rupture. With sacrifice. With the terrifying possibility that real art doesn't soothe the soul. It wounds it.

Bataille imagines the artist as someone who must journey to the very edge of death and come back changed. If you're lucky, you return with a glimpse of the "exploding city that constitutes the meaning of life." If you're unlucky, you don't come back at all.

Sure, you could read that metaphorically. Where Plato's philosopher leaves in search of light and truth, Bataille's artist chases death and fleeting ravishment. But think of artists who actually destroyed themselves for the work: through drugs, alcohol, obsession, or the pressure of trying to represent the unrepresentable.

Consider Pliny the Elder, who literally died trying to get a closer look at an exploding volcano. He sailed toward Vesuvius while everyone else fled, so he could observe it up close and take notes. That's Bataille's artist: obsessively curious, recklessly devoted, and probably doomed. He wanted a clearer view, and it killed him. According to Bataille, the artist must accept that risk.

The viewer (you) gets to sit comfortably on the outside. You don't have to get close to the volcano. You don't have to go mad, or suffer, or almost die. The artist does that for you. They're the sacrificial victim. You're just the tourist taking pictures of the shrine.

So why must it be that extreme? Can't art be meaningful without violence or death? Can't vulnerability be enough?

Not really.

According to Bataille, you can't fake transgression. There is no ethical consumption of revelation. Earning it means being willing to lose yourself in the process.

Bataille draws a line between sacred violence and aesthetic form:

- Religious art depicts martyrs torn apart for our sins.

- Modern art rips objects apart to show us how they work.

Cubists and Surrealists deconstruct everyday things (bottles, bodies, guitars) like ritual sacrifices. These aren't just abstract games. They're stand-ins for crucifixions. That's their appeal. The artist dismembers form so we don't have to.

But even the grotesque must entice. Art must attract even when it disgusts. Art that repels fails. A crucifixion that makes you look away isn't doing its job. You must want to see. To get closer. To feel the heat of the thing that's killing the artist.

Artists are cursed with an inability to forget the infantile, terrifying questions:

- Why am I here?

- What does it mean?

- Why must I die?

Most people learn to tune those out. They get jobs. They fold laundry. But artists? They keep turning over stones, looking for meaning. Eventually, they arrive at the inevitable suspicion: Maybe the only real answer is found in death, immediately followed by the realization that the answer is useless if you're actually dead. So they go right up to the edge to get the best view and bring it back (packaged) for us. That's the cruel practice. Batille's artist is a martyr, sacrificing safety and sanity to bring us a fleeting glimpse of truth.

If you're an artist, Bataille wants you ruined. He wants you naked before the gods. He wants your ego stripped, your comfort obliterated. It's not about beauty. It's not about meaning. It's about getting close enough to the fire to singe your eyelashes and coming back with a sketch.